Since Trump’s first presidential victory in 2016, the idea of “economic anxiety” or “economic threat” as a way of explaining Trump’s appeal has been commonplace. Presumably, this would operate through people’s economic ideology, as displayed in this diagram:

1 Less materialist authors pointed out that, perhaps instead of/in addition to the (purely) economic threat these people felt, they also felt a status threat (here, but here).

flowchart LR

A["Exposure to Economic<br/>Vulnerability<br/>(immigration, outsourcing,<br/>capital vs. labor)"] --> B["Preferences toward<br/>Protectionism and<br/>Restrictionism"]

B --> C["Support for Trump"]

style A fill:#357BA2,stroke:#DEF5E5,stroke-width:3px,color:#DEF5E5

style B fill:#3E356B,stroke:#DEF5E5,stroke-width:3px,color:#DEF5E5

style C fill:#0B0405,stroke:#DEF5E5,stroke-width:3px,color:#DEF5E5

linkStyle 0,1 stroke:#DEF5E5,stroke-width:2px,length:20

This “economic anxiety” argument, though, is just one instance of a broader set of economic self-interest arguments, which are littered throughout the social sciences. Concerns about housing value lead to NIMBYism; union membership predicts vote choice; unemployment increases sentiment toward the welfare state; economic recession leads to punishing incumbents; having few credentials causes a preference for restrictionism.

2 Though the economic self-interest thesis is descriptive, it also appears in prescriptively. For example, in the 1980 debate between Reagan and incumbent Carter, Reagan asked in his closing remarks, “Are you better off than you were 4 years ago? Is it easier for you to go and buy things in the stores than it was 4 years ago? Is there more or less unemployment in the country than there was 4 years ago? Is America as respected throughout the world as it was? Do you feel that our security is as safe, that we’re as strong as we were 4 years ago?” Notice that the first two of his ‘operationalizations’ of being better off are economic. He was asking voters to think of economic interests when deciding whom to vote for. It also appears prescriptively in the lament, “The working class is voting against it’s self-interest.” Here, interestingly, economic self-interest appears as a desirable thing people are failing to do – so it’s prescriptive but not descriptive.

This study is part of that universe. Here, we’re asking, If learning that your economic horizon is bleak (or positive), do you shift leftward (or rightward) in your economic ideology? Specifically, do you endorse more socialist (or capitalist) norms and descriptions of the world?

In writing the materials for the study, we took advantage of the fact that artificial intelligence is widely believed be on the precipice of revolutionizing (at least) the labor market. In the history of research on economic self-interest, it has always been those who are already less well-off who find out they are even worse off. For example, it was the declining manufacturing sector that was hit by the ‘China shock’ of the 1990s. AI is unique in the history of economic shocks because it at least has the potential to hit those at the top hardest. This enables us to credibly inform participants who may be successful in the labor market that that success might be coming to a sudden end.

Somewhat unique among other studies in this area, we wanted to pinpoint the relative status facet of economic well-being and try to find out what would happen when people’s relative economic standing increased or decreased. Specifically, does this change in relative status change people’s views of the most desirable economic institutions (understood in a broad sense to include the government’s role in the economy as well as the structural characteristics of an economy)? Soon I will get to why I’m not sure we pinpointed that aspect of economic interest so precisely, but that is best accomplished in the context of describing the sample and the study itself.

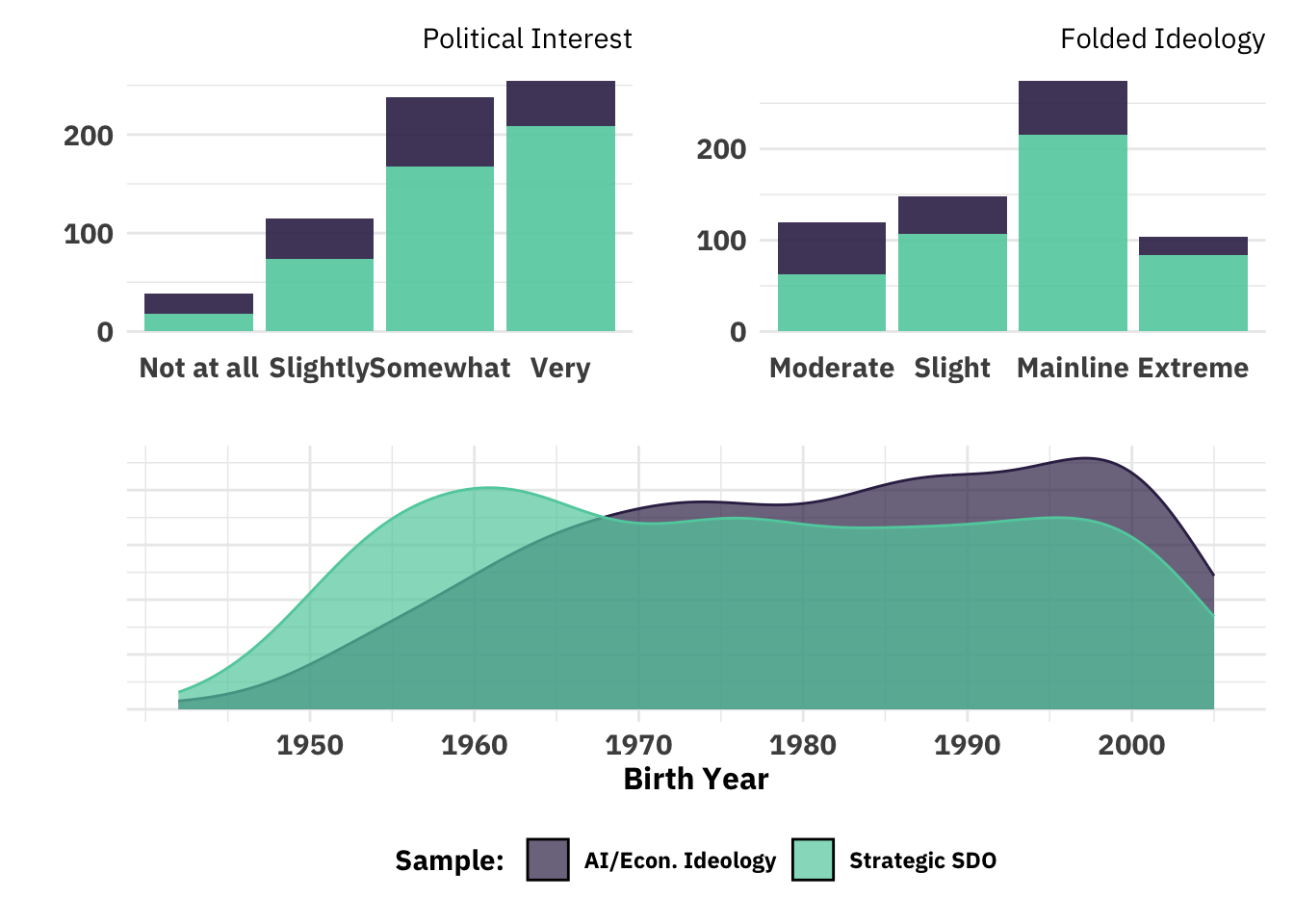

Sample

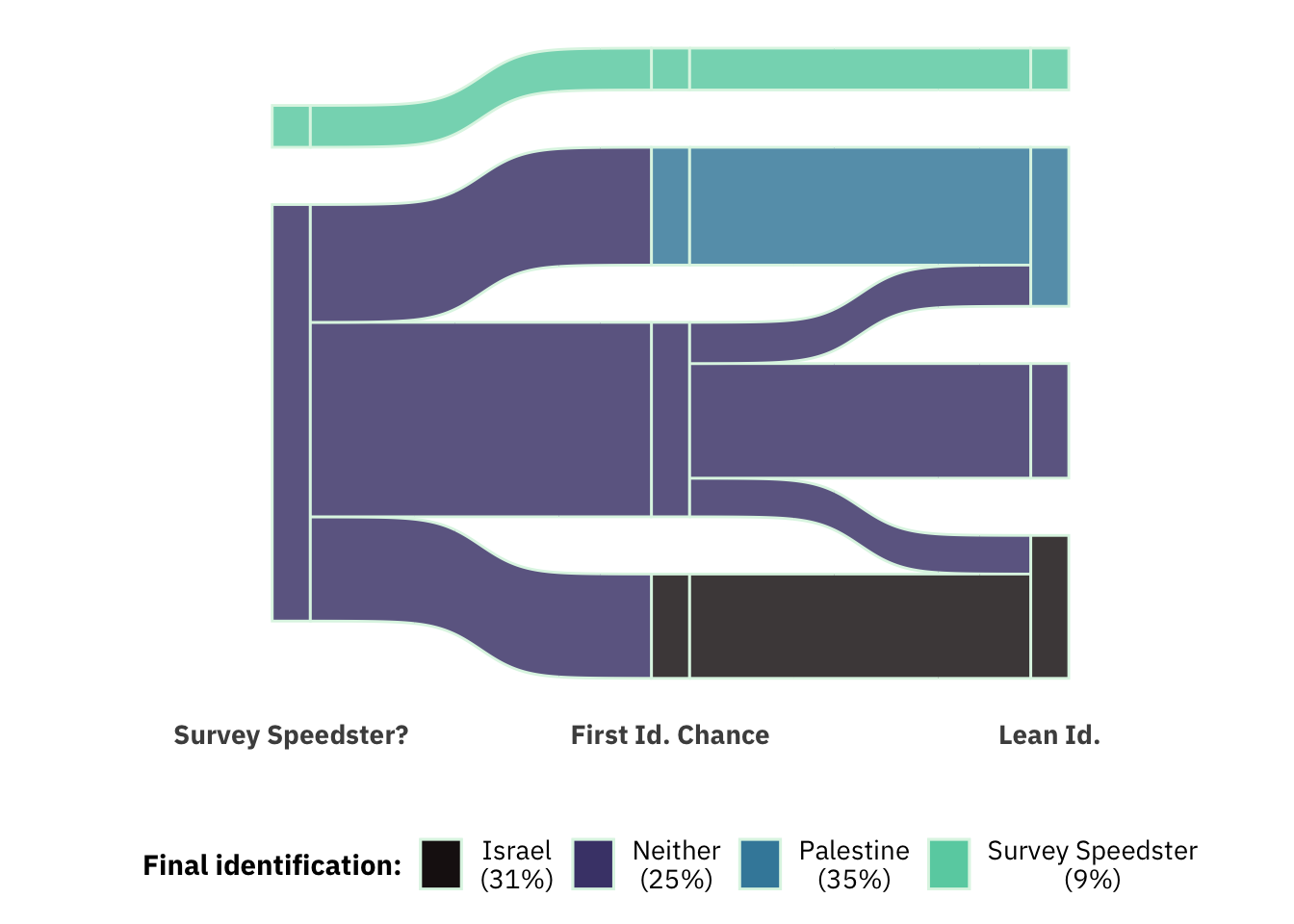

Before we begin, a brief word on the sample. The respondents are only one arm of an experiment I ran with Adam Panish in mid-2024. We started with a demographically representative sample of around 700 from CloudResearch, but most of the participants went into an experiment designed to test a ‘strategic social dominance’ hypothesis we had (see the post). Those that ended up in this experiment did so because they did not identify with either the Israeli or Palestinian sides of that conflict. Specifically, after answering demographic questions, participants were asked if they identified with either Israel or Palestine in the Gaza conflict (with Neither being an explicit third option). In a follow-up question, those who chose Neither were asked if they lean toward either side. Those who identified with either side, either in response to the initial or follow-up questions, were shunted into the Israel-Palestin’ study arm. You can think of that experimental arm as the primary one, but for its materials to make sense we needed subjects that identified with one of those two sides. Those for whom the materials would have been meaningless wound up here. Because most subjects did identify with one of the two sides, this AI-dislocation study had 204 subjects enter it, 178 of which passed a minimal requirement of having spent at least 15 minutes on the study and are included in these results. This, then, is a small sample by post-Replication Crisis standards.

Because they’re fun, here’s a Sankey diagram showing who ended up in the sample:

In case you continue to be curious about the sample, there is more information in the appendix.

Experimental Treatment and Outcomes

To set up the experimental treatment, all participants read a short, two-paragraph excerpt from an article about how AI would upend the economy. The article emphasized the two points that “AI will reshape wealth and income distribution, [and] the ultimate winners and losers of the coming AI revolution are far from obvious” You can read the full text below. We then gave them what we sold as a personality test in the style of THESE FOUR QUESTIONS YOU’D NEVER SUSPECT SAY EVERYTHING ABOUT YOUR FUTURE. The quiz was simply four questions that were prima facie relevant to one’s economic prospects (questions below), though we told participants that we would be able “to calculate the most likely effects of AI on your future employment.” After they answered the questions, we told them we were processing the results with a fancy algorithm. This was not the case. In reality, we randomly assigned half of participants to receive a positive message and the other half to receive a negative message. Those messages are printed below:

3 It was really a pastiche of information I picked up

4 The subjects also saw those images. They were displayed on the screen while the participant was waiting for the oracular algorithm to calculate their future.

Negative Feedback

Your responses indicate a potential vulnerability to the disruptions AI will bring. Of course, within each group of respondents with similar profiles, some will do better and others worse. That said, respondents with your socio-occupational profile are projected to move down in the income distribution. As a group, people with such profiles will likely lose prestige and relative income.

Positive Feedback

We have good news! Those with your profile are projected to do well in the upcoming labor market transformation, sitting atop the income distribution. As AI becomes more important in the economy, you and similar respondents are likely to experience gains in prestige and income relative to those with different profiles.

5 Notice the spatially-encoded status language in the feedback: The unfortunate souls are likely to “move down in the income distribution” and “lose prestige and relative income,” while the happy ones will “sit atop the income distribution and”experience gains in prestige and [relative] income.” The spatial bit may not be important, but George Lakoff approves.

That was it! Maybe it’s hard to believe, but that kind of thing passes for a treatment in political psychology. You might notice that the main point of the feedback was to impress them that they will lose out in a relative sense. That is, we say nothing about their absolute quality of life in the post-AGI regime, we instead focus on relative income, their place in the income distribution, and prestige (classic relational good). This specificity was very important to us at the time of writing the materials, because we had in mind a specific theory about how a person’s relative standing is an important input to their attitudes about supporting norms. Though I still give credit to the theory, I do not think it’s profitable to think about this experiment in such specific terms. Instead, the treatment represents a kind of economic shock and the outcomes will measure broad left-right economic ideology.

Check yourself, check your manipulation

To gauge respondents’ opinions of the four-question quiz and the ensuing feedback, we asked them, “Briefly, what do you think of the results of the accuracy of feedback you just received?” and they responded in an open text box. I also had my crackerjack research assistant “Claude” code all the responses as positive, negative, or neutral in order to see if those in the positive feedback treatment group actually a positive evaluation of the feedback.

6 I told Claude, “You are an expert coder of open-ended responses. Below you will see five responses to the question, "What do you think of the results of the accuracy of feedback you just received?" For each, create a set keywords that describes the respondent’s stance toward, or beliefs about, the feedback. The only constraint is that you must describe the stance as positive, negative, or neutral as the first of the keywords. Example responses:

[positive, accurate, exciting]

[negative, inaccurate]

[neutral, irrelevant]

Your response should be five sets of keywords in square brackets separated by newline characters.”

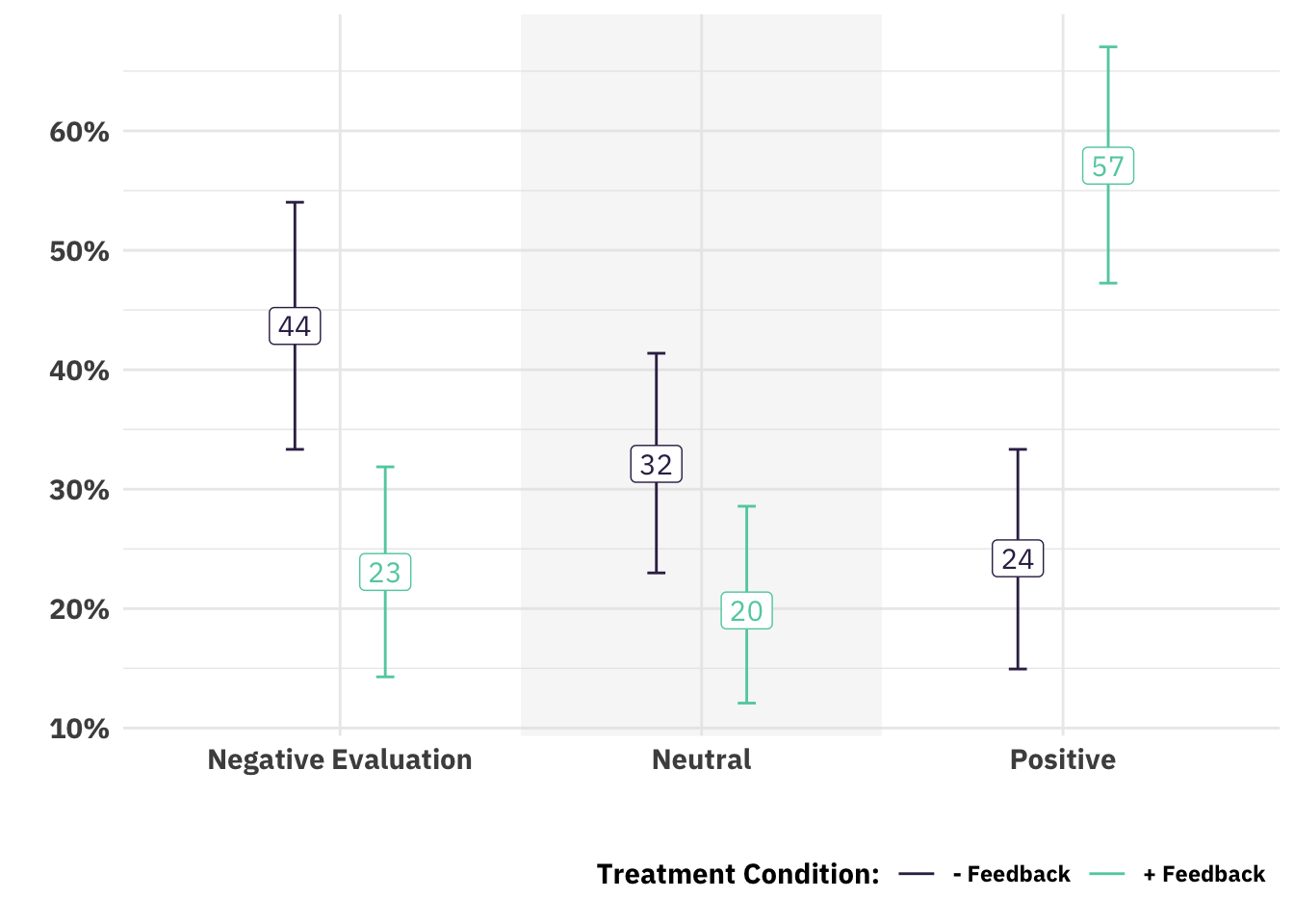

The plot shows the probability of a negative, neutral, or positive evaluation between the two treatment groups:

Now that’s social science! If you give people negative feedback, people will think (more) negatively of that feedback. If you give people positive feedback, people will think (more) positively of that feedback. But you might also worry about the fact that, among the group that received positive feedback, a full 23% had a negative evaluation of it (and only 57% had a positive opinion of it). As I’ll mention later regarding respondent inattentiveness, ideally I would have had a larger sample so as to be able to look at treatment effect heterogeneity among different groups of treatment evaluation. Given my limited sample size, the most rectitudinous thing I can do is display these data an say C’est la vie.

Here are some illustrative responses for the raw-data crowd:

Positive Evaluations

- “The results are interesting and I would say accurate”

- “The result makes me happy. But I’m not sure if that would happen.”

- “I extremely relieved. I am also thankful for those results.”

- “Accurate”

Neutral Evaluations

- “Immaterial as I am close to retirement”

- “Okay”

- “I believe AI will take over portions of my job”

- “Hard to say, maybe 50% accurate?”

Negative Evaluations

- “I doubt it’s accurate and I don’t trust it for a second.”

- “I think it’s made up”

- “I think it is fake and predetermined by the researchers.”

- “Totally inaccurate. I am retired and get my income from SS and savings. I’ll be fine.”

7 One thing I learned in all this is to screen out retirees if you’re (even directly) studying labor market dynamics.

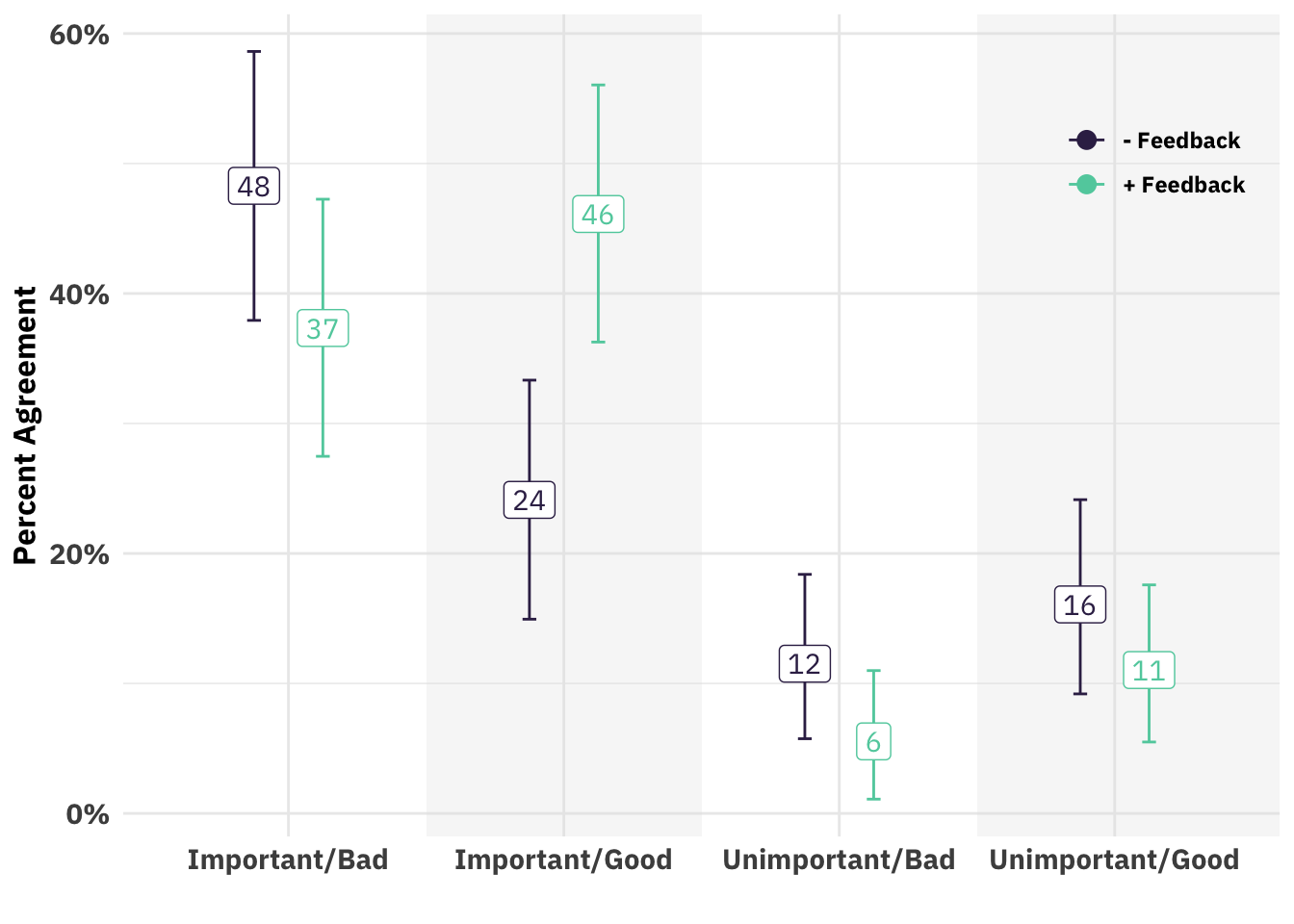

In addition to seeing what people thought of the feedback, we can (and did) ask respondents what they thought of AI, generally. We asked the following question with response categories below:

“More generally, what is your opinion of artificial intelligence?”

- Important and a force for good (Important/Good)

- Important and likely bringing about negative consequences (Important/Bad)

- Mostly unimportant, but will cause small positive changes (Unimportant/Good)

- Mostly unimportant, like to cause negative consequences if any (Unimportant/Bad)

8 This bold text to the right of the response did not appear to the participants, but allows you to link the response wording to the labels in the plot below

Similar to the last plot, the plot below gives the probabilities of selecting one of those four responses broken down by treatment group.,]

Here, our treatment was (directionally) effective: those who received positive feedback were almost twice as likely to pick the statement ‘AI is important and a force for good’ than those who received negative feedback. The positive-feedback receivers were also half as likely to say that AI is unimportant and bad (6% versus 12%, but this effect is less dramatic in absolute difference, which is what pops out on the plot).

9 This is one of those cases where a control group would have been nice.

We thanked them for completing that exercise and let them know we wanted to “know about your economic views more generally.” These economic views were the outcome variables of the study.

Results

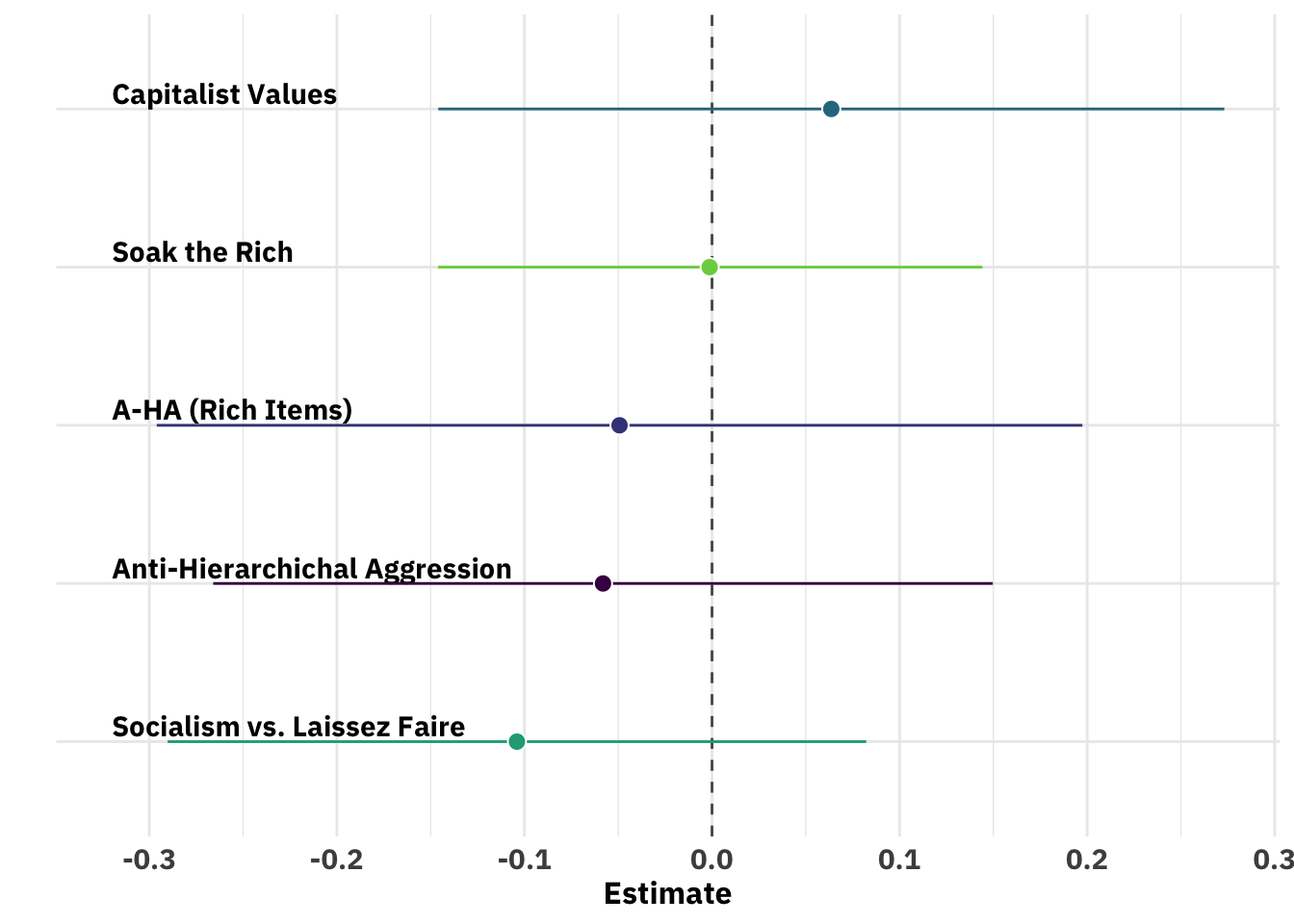

Respondents’ economic views were measured with four groups of outcomes:

- A single item measuring respondents’ willingness to punitively ‘soak’ the rich even at the cost of redistributing less to the poor. Its authors describe it as measuring a “wealthy-harming preference.”

- A scale consisting of seven items measuing ‘capitalist values.’

- A 10-item scale measure (dis)agreement with statements expressing either a socialist or laissez faire worldview.

- The 13-item anti-hierarchical aggression subscale from Costello et al.’s (2022) left-wing authoritarianism scale.

10 Doing my best imitation of a p-hacker, I also extracted post hoc four items from this scale that mention “the rich” after seeing that they form a unique cluster. That’s the genesis of “A-HA (Rich Items)” in the plot below.

This is the results section for those who want to read the short of it. For those interested in the long of it (looking at individual items instead of pre-summated scales, etc.), a longer version of this section appears in the appendix.

I analyzed each outcome by regressing it on nothing other than treatment (positive feedback, negative feedback). Specifically, I regressed the outcome onto a dummy for having been in the positive treatment group. This means that the expected effects are negative, since larger outcome values mean a more ‘lefty’ response and larger treatment variables (i.e., 1 instead of 0) means ‘in the positive feedback group (and thus not negative feedback group).’ For those whose eyes glazed over reading the immediately foregoing, no worries. The results are actually very easy to interpret. In fact, I can summarize the results with the following plot:

11 In the case of the three scales, I performed this regression as the structral part of a measurement model where each scale item was taken as an indicator of a latent (endogeneous) variable. For those who care, I used lavaan::sem() in R. In the case of the socialism/laissez faire items, I treated the indicators as ordinal. In the case of the seven-category response to the A-HA items, the reported results come from a model treating the indicators as interval variables. The results don’t change either way.

As you can see, the uncertainty bars for all four (/five) outcomes overlap 0, meaning that none of the results are statistically distinguishable from 0 (ergo no “significant” effects). The point estimate for the capitalist values scale even ruins the story that at least all point estimates were on the expected side of 0.

Post-Mortem

So, wherefore this null finding? Leaving the possibility that the null is true for last, let’s briefly run through the ‘boring’ possibilities.

First, could it have been respondent in inattentiveness? As mentioned in the sample section, I excluded participants who took the survey in quicker than 15 minutes. That is an extremely conservative cutoff in the sense that it was really only remove the people who did a speedrun through this thing. Ideally, what I would do were the sample larger, would be to calculate the treatment effect among different subsets of respondents defined by their level of attentiveness (which time in survey is a proxy for). For example, one could do a tercile split of response times to divide them into the quickest, middle, and fastest terciles. If those who were more attentive ‘absorbed’ more of the treatment (and time is a good proxy for attentiveness), then we would see the treatment effect grow across the terciles.

Second, perhaps the sample size was too small. Every survey experiment is an exercise in signal detection, sample size is a key signal amplifier, and in this case the sample just couldn’t beat out the noise. Given that so many of the estimates were on the “right side” of zero, I could choose to hold onto this thread of hope. Regardless, I also have to chastise myself a little, because if this had been a study with big insitutional backing the fact that I didn’t to an ex ante sample size calculation would be quite damning – perhaps there was no real chance I would have seen a true positive from any plausible effect size.

12 See here for an example of how one would determine a minimum viable sample size.

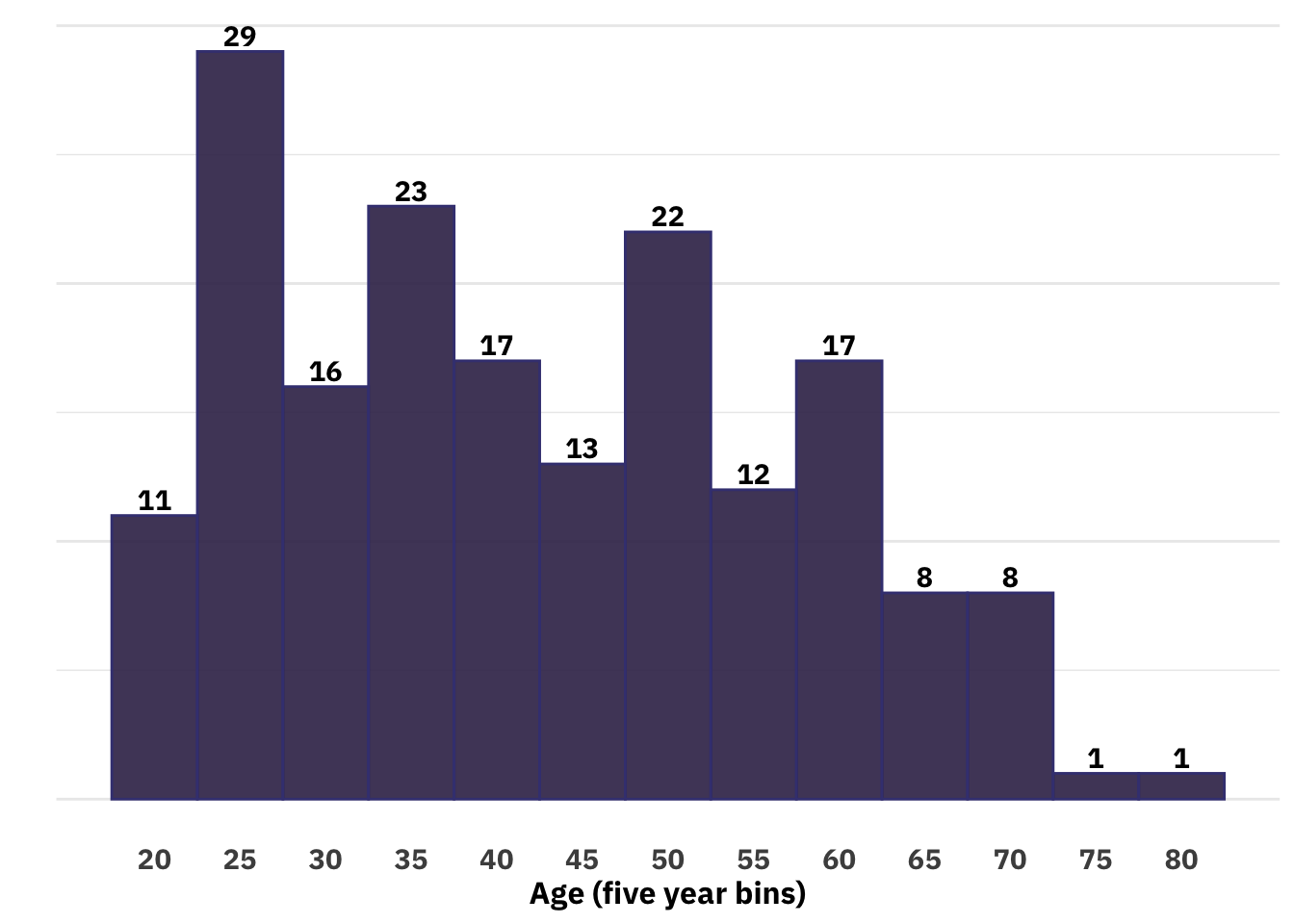

Related to the small sample size, there is the issue that the sample might be of the wrong type (age-wise).

Let’s say that you think the treatment could only be effective among an age subgroup defined by being less than a certain age. For example, you might think that those 55+ are close enough any news they hear about the labor market, they think, “Well, sounds like a problem for the next guy to sort out!” In that case, you could look at the cumulative distribution, draw a vertical line up from the x-axis where 55 would be, eyeball the point where it intersects the cumulative distribution, and that point’s y-coordinate is what proportion of our sample even could have produced a theoretically interesting result. You can use this to calculate something like an “effective sample size,” which would be some (smaller) proportion of the nominal sample size of 178.

13 In this case it would be 75%

14 For example, \(F(\text{age}) \times\) 178, where \(F(\text{age})\) is the \(y\)-coordinate given a certain age, a number between 0 and 1.

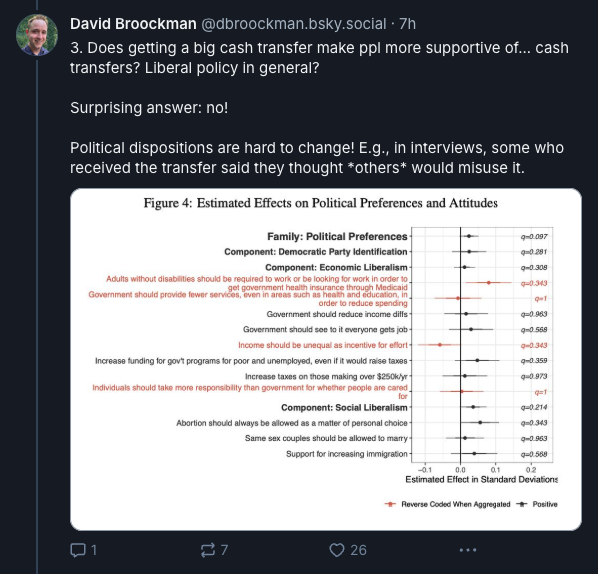

So, the sample might be inattentive, generically too small, or too small in the demo. But another reason for the null accuses the researcher a bit more. That is simply that the materials were shite-proximate. As I show in the appendix, the outcome variable scales really do seem to be picking up meaningful differences among the respondents, so bad dependent variables does not seem to be the culprit. That leaves a potentially ineffectual manipulation. In its favor, you wouldn’t be able to pick out the stimuli used here from a lineup of lab psychology studies. On the other hand, you might point out that psychology was until very recently a methodological cesspool. In this particular case, I’d ask if we even should be trying to manipulate beliefs about the self, in this case perceived (relative) wealth or status, through (mostly) passive, (mostly) text-only interventions. Even economic windfalls, such as winning a lottery or participating in a universal-basic income experiment, seem to have only inconsistent effects on economic ideology ( These two papers find the effect, while these two largely do not). If that is the case, then what hope did we have in trying to manipulate economic views with some text? I think this is an extremely strong point. If actually changing someone’s socio-economic status doesn’t reliably shift their beliefs, then how would telling people that their socio-economic status might change possibly affect their beliefs?

15 Terminus technicus, don’t look at me.

16 This doesn’t rule out using humble manipulations such as those here, as long as they use normative argumentation rather than appealing weakly to self-interest.

Lastly, could the null be true? Yes, of course! But I find it very implausible that information about one’s economic future has no impact on one’s economic ideology. Just imagine that you are a down-on-your-luck center-left person in this study and you “find out” that your economic prospects are bleak. In happier moments, you might slightly disagree with “We need to replace the established order by any means necessary,” but mightn’t the camel’s back have broken with the information that your economic future is downhill and now you instead slightly agree? I don’t know. It’s worth a thought.

17 Yes, I know. The null is never going to be true, but you know what I mean. The actual effect is smaller than anything we’d care about.

Appendix

Results (Long)

For the time-wealthy, I have a more detailed break down of the outcomes and results. Instead of presenting the scales as aggregates, you can see them disaggregated by individual question. I also show their partisan and ideological breakdowns, so you can get an idea of whether or not you think these scales are measuring anything at all!

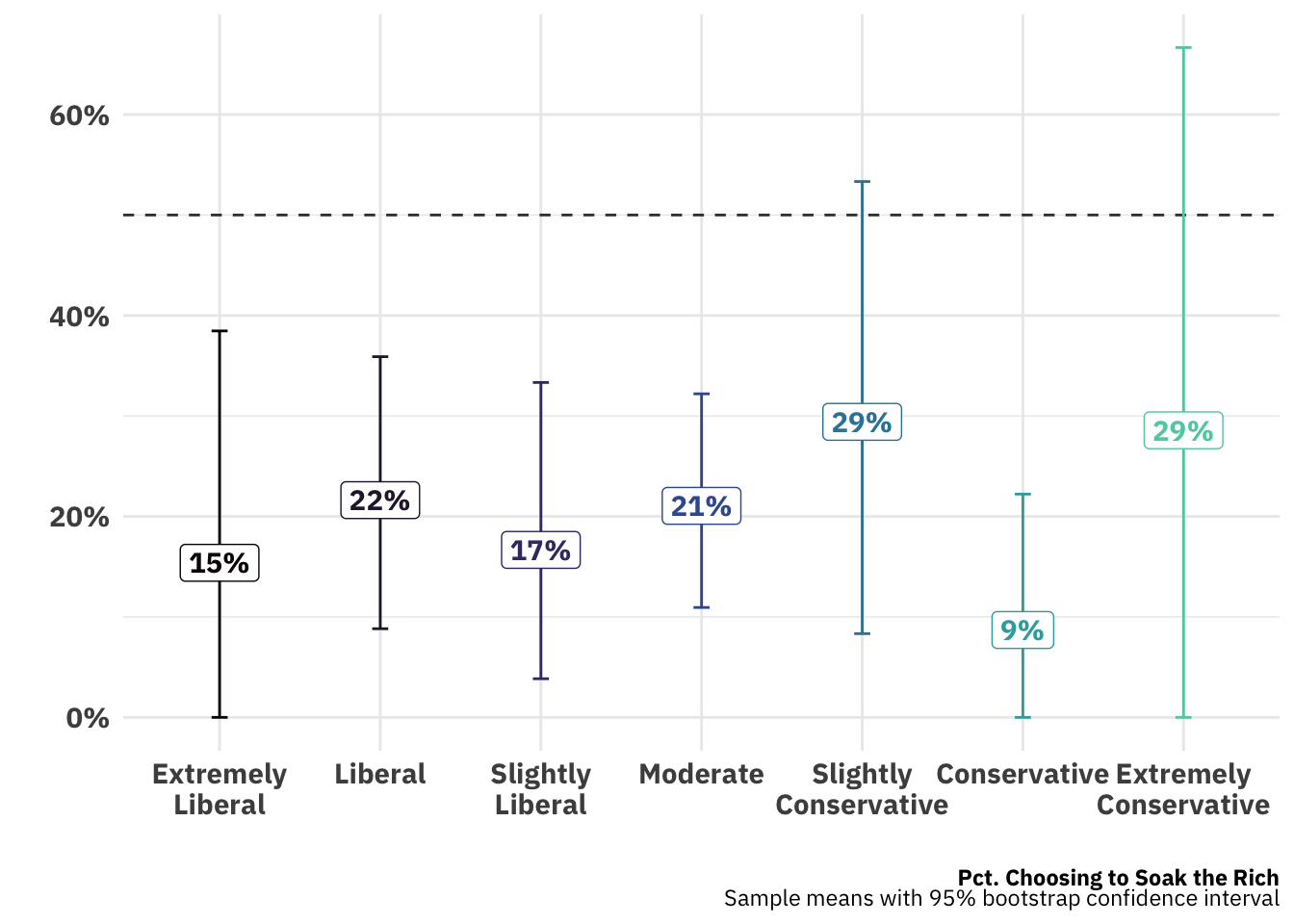

To Soak or Not to Soak

The first item presents respondents with the following two scenarios and asks them to select the one they prefer:

- The top 1% wealthiest individuals pay an extra 50% of their income in additional taxes, and as a consequence of that the poor get an additional $100 million (the extra 50% in taxes paid in former fiscal years leaving the wealthiest with relatively less taxable income.)

- The top 1% wealthiest individuals pay an extra 10% of their income in additional taxes, and as a consequence of that the poor get an additional $200 million (the extra 10% in taxes paid in former fiscal years leaving the wealthiest with relatively more taxable income.)

19 The bold text also appears bold in the experiment.

This item is nice because it pits two (potential) desires against each other: the punitive desire to harm the rich and the make the less well-off better-off. If you think that e.g., ‘Every billionaire is a policy failure’, then you’ll be drawn toward the first option. If, however, you think that the contemporary focus on inequality is a misguided worry about the poor, you’ll be drawn to the second.

20 A sophisticated survey taker might also have positional and efficiency considerations, but I’ll leave those aside.

Unfortunately for me, but also consistent reasonable prior of minimal effects, there was no significant effect of the treatment on this outcome. Had I seen the plot below, which shows that punitive taxation (perhaps surprisingly) does not change that much across the ideological spectrum, the null finding should not be surprising.

And although we see substantively different point estimates (e.g., liberals are more than twice as likely to assent than conservatives), the within-group heterogeneity is such that we would have needed a much larger sample to detect any differences caused by the AI treatment.

21 For the curious, Sznycer et. al (2017) found that “dispositional envy” was the only reliable predictor of this outcome, and Lin et al. (2024) similarly found a strong (and unique) association between they called “malicious envy” and this measure. So perhaps this measure only works to the extent that a treatment induces envy.

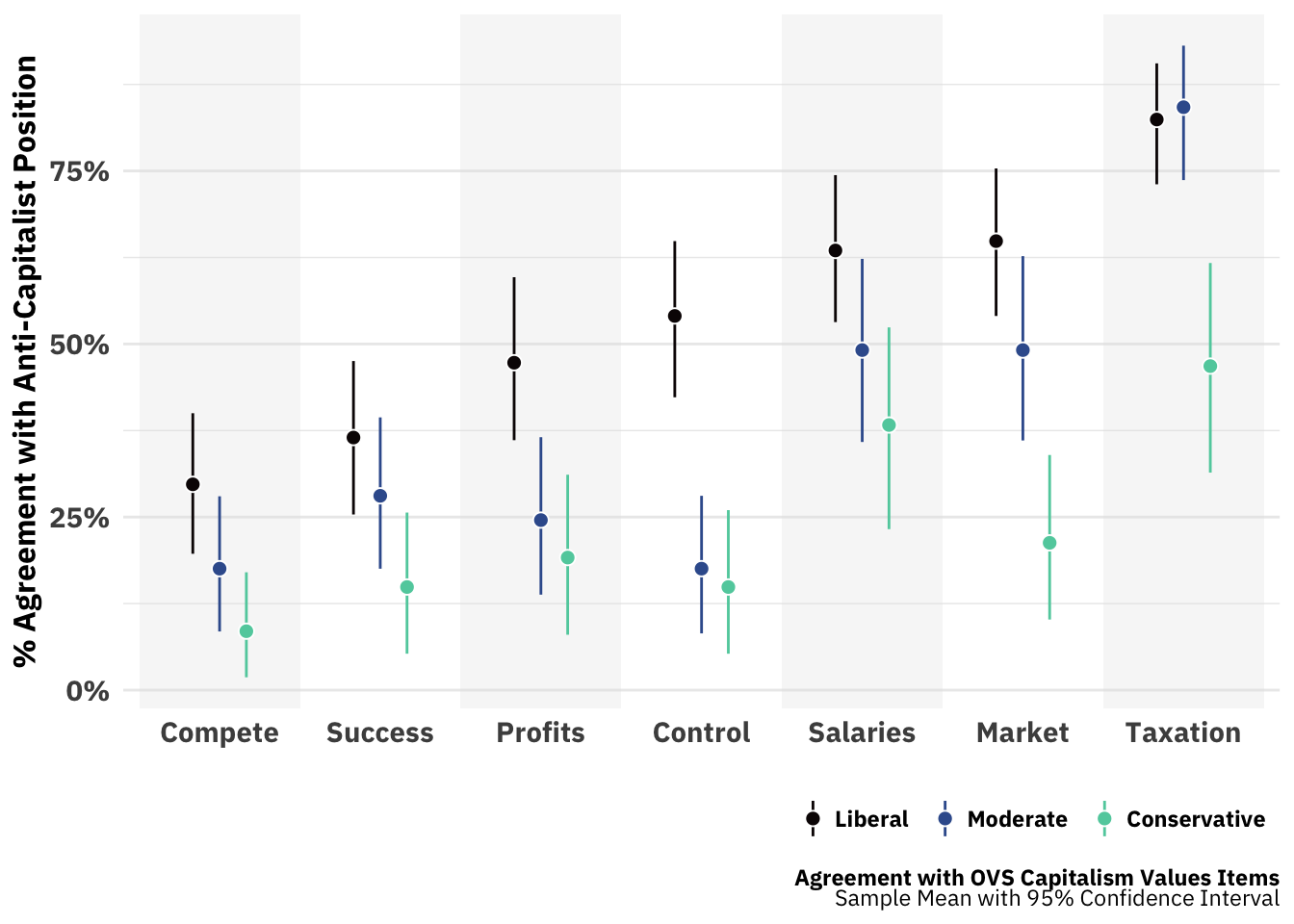

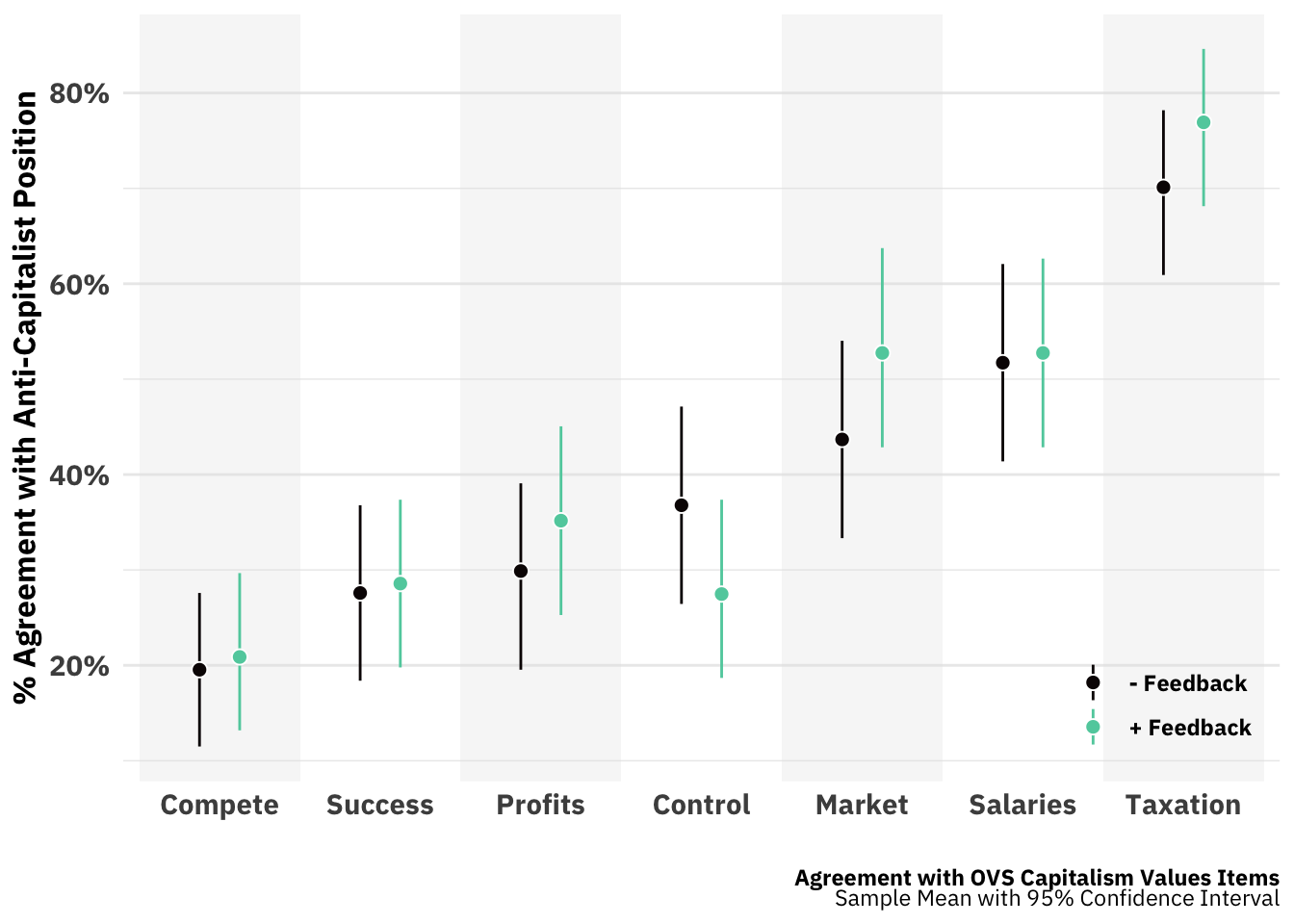

Capitalist Values

We took the following seven items from the capitalist values scale from Chong, McClosky, and Zaller’s (1983) Opinions and Values Survey.

22 Their original capitalist values scale contained 28 (!!) items.

- Getting ahead in the world is mostly a matter of …

- good luck

- ability and hard work

- When it comes to taxes, corporations and wealthy people …

- don’t pay their fair share

- pay their fair share and more

- Free-market economies …

- survive by keeping the poor down

- give everyone a fair chance

- The profits a company or business can earn should be …

- strictly limited by law to a certain level

- as large as they can fairly earn

- Competition, whether in school, work, or business …

- is often wasteful and destructive

- leads to better performance and a desire for excellence

- Most business people …

- do important work and deserve high salaries

- receive more income than they deserve

- The government taking over a larger share of the economy to limit the profit motive would be …

As with the ‘soak the rich’ item, each capitalist values item presents respondents with a binary choice (this time in a sentence-completion format. One choice is (directionally) congruent with a pro-capitalism worldview while the other choice is not. For the purpose of this appendix, however, I will eschew theorizing and merely note that the items ‘work’ in that they pick up different priorities among ideological groups:

23 If the reader is interested in an analysis of America’s twin traditions of capitalism and democracy, I encourage readers to go read either the original 1983 article whence these items came or McClosky and Zaller’s book, The American Ethos: Public Attitudes Toward Capitalism and Democracy, that came out the following year.

Considering the items as a scale, they have acceptable internal coherence (Cronbach’s \(\alpha=\) 0.73, \(\Omega=\) 0.73). To use concepts from item-response theory, you can see from the plot that a scale composed of these items spans a good range of difficulty and all its items have prima facie discrimination, as they reliably order the ideological groups. Even with decently cromulent scale in hand, I fail to detect any statistically significant difference between the positive and negative feedback groups.

24 Briefly, an item’s difficulty indicates how ‘extreme’ you have to be on a trait in order to answer the item in the affirmative. I say this scale has a good range of difficulty because you have items ranging from <25% agreement to >75% agreement among the moderates.

25 An item’s discrimination indicates the extent to which it distinguishes between those with higher and lower values of the trait.

You’ll notice that a) none of these difference are significant and b) even when we might be nearing the ignis fatuus of “marginal” significance, the results are inconsistent. When asked about the government taking over a larger share of the economy (the control item), those who received negative feedback were more likely to assent. However, on an item that really should be tapping the same ideas (‘Do free-market economies keep the poor down or give people a fair chance’), the pattern is reversed.

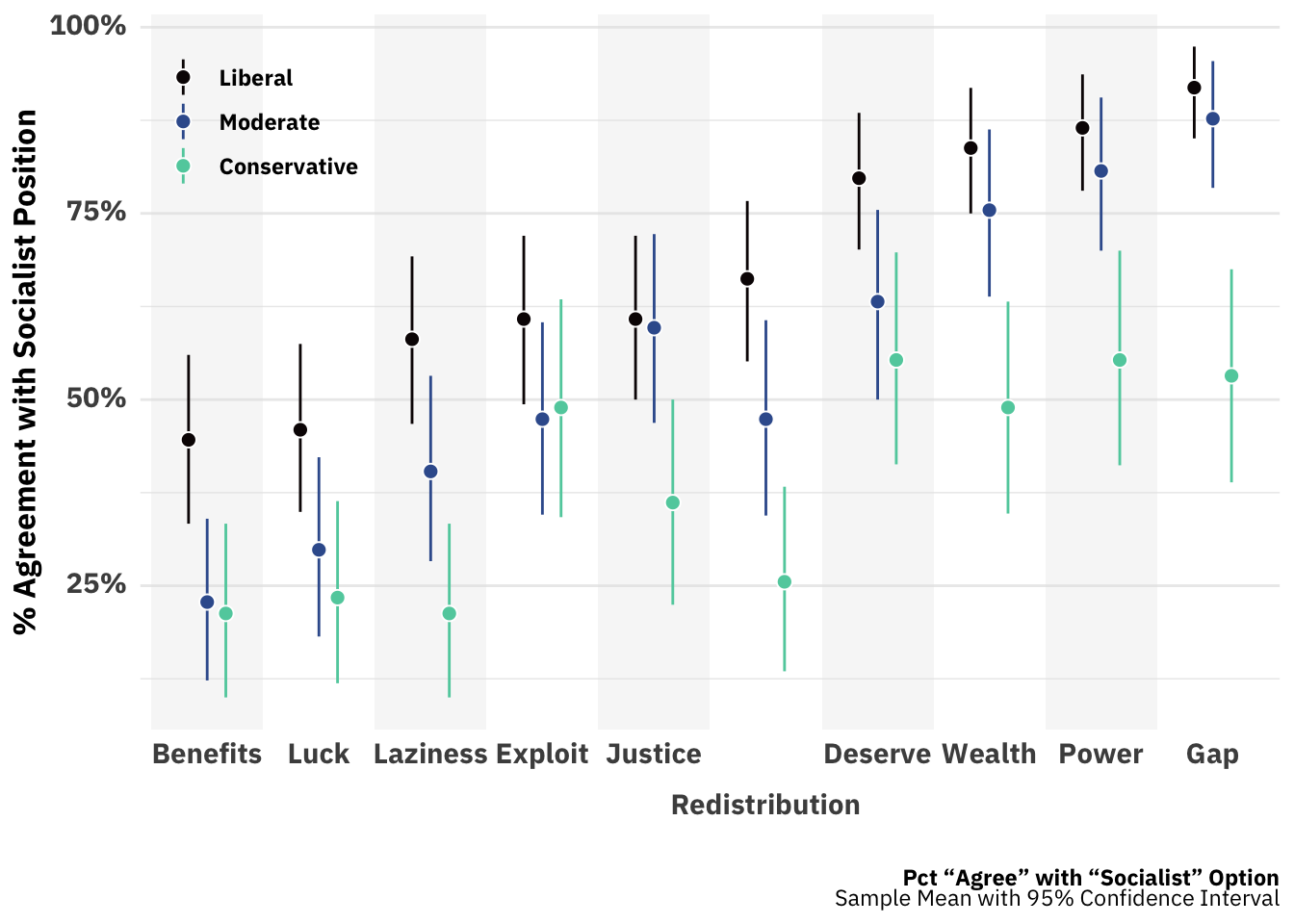

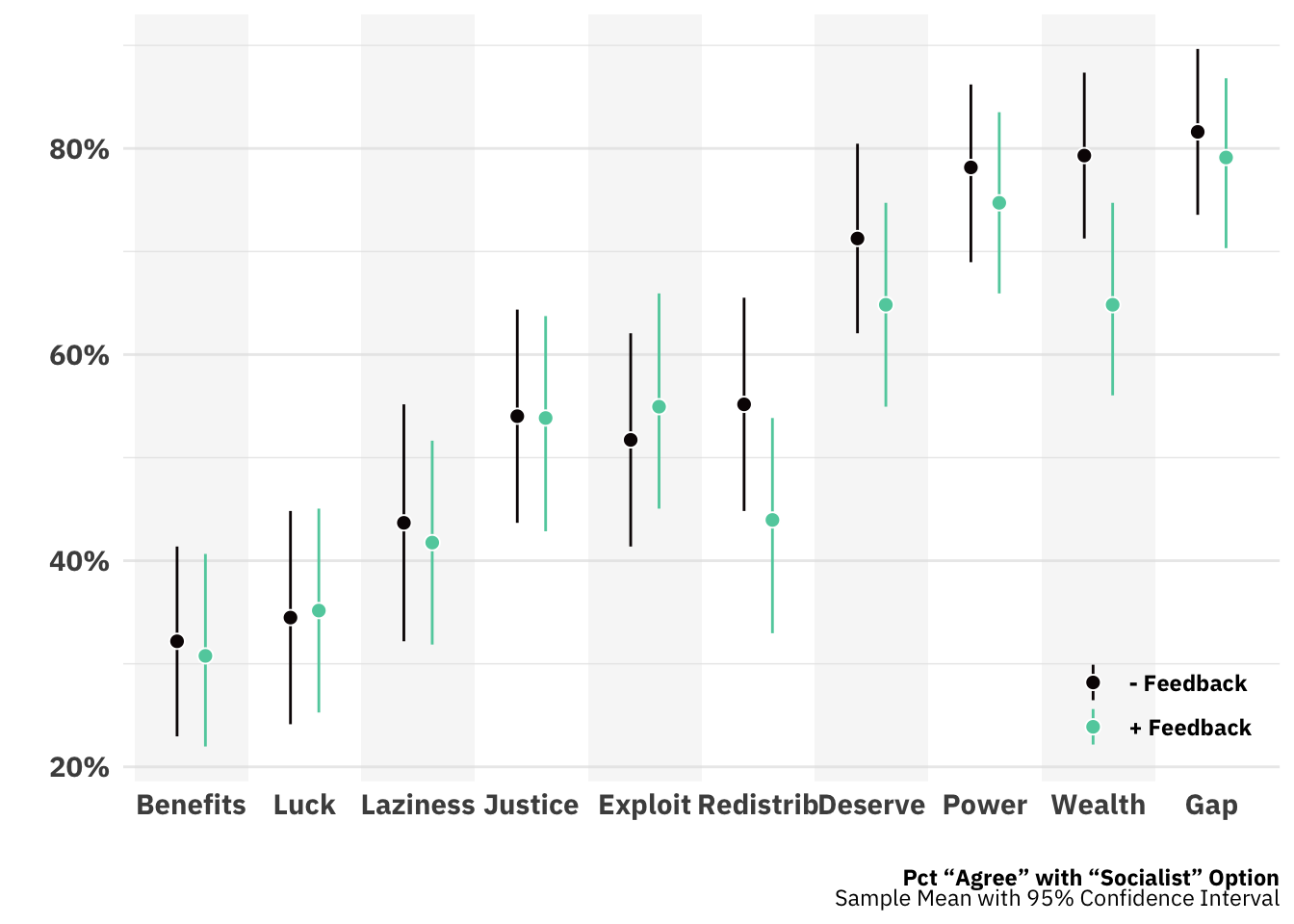

Socialist/Laissez Faire Items

Another tranche of items came from Heath, Evans, and Martin (1994). As with the previous scale, we culled out those whose language seemed a throwback to an earlier era using a sophisticated NLP technique called “mid-Millennial/elder Gen Z savoire faire.”

26 Apparently we also added at least a couple of items from Leslie McCall’s research, but I can no longer find their exact source.

Unlike the previous sentence-completion items, these were presented in a grid format:

27 In case the image is too small to read the text, click here to read the questions.

One thing I always worry about when I (or anyone else) use a grid is that respondents will click in a straight-line. I checked and only two respondents did this.

28 Occasionally I myself do this when I’m at a doctor’s office and I’m given a bunch of possible pre-existing conditions I don’t have.

Again, the scale ‘worked’ in that it was internally consistent (Cronbach’s \(\alpha=\) 0.73, \(\Omega=\) 0.83), traversed a wide range of assent, and differentiated liberals and conservatives.

Also again, no consistent differences between the two treatment groups.

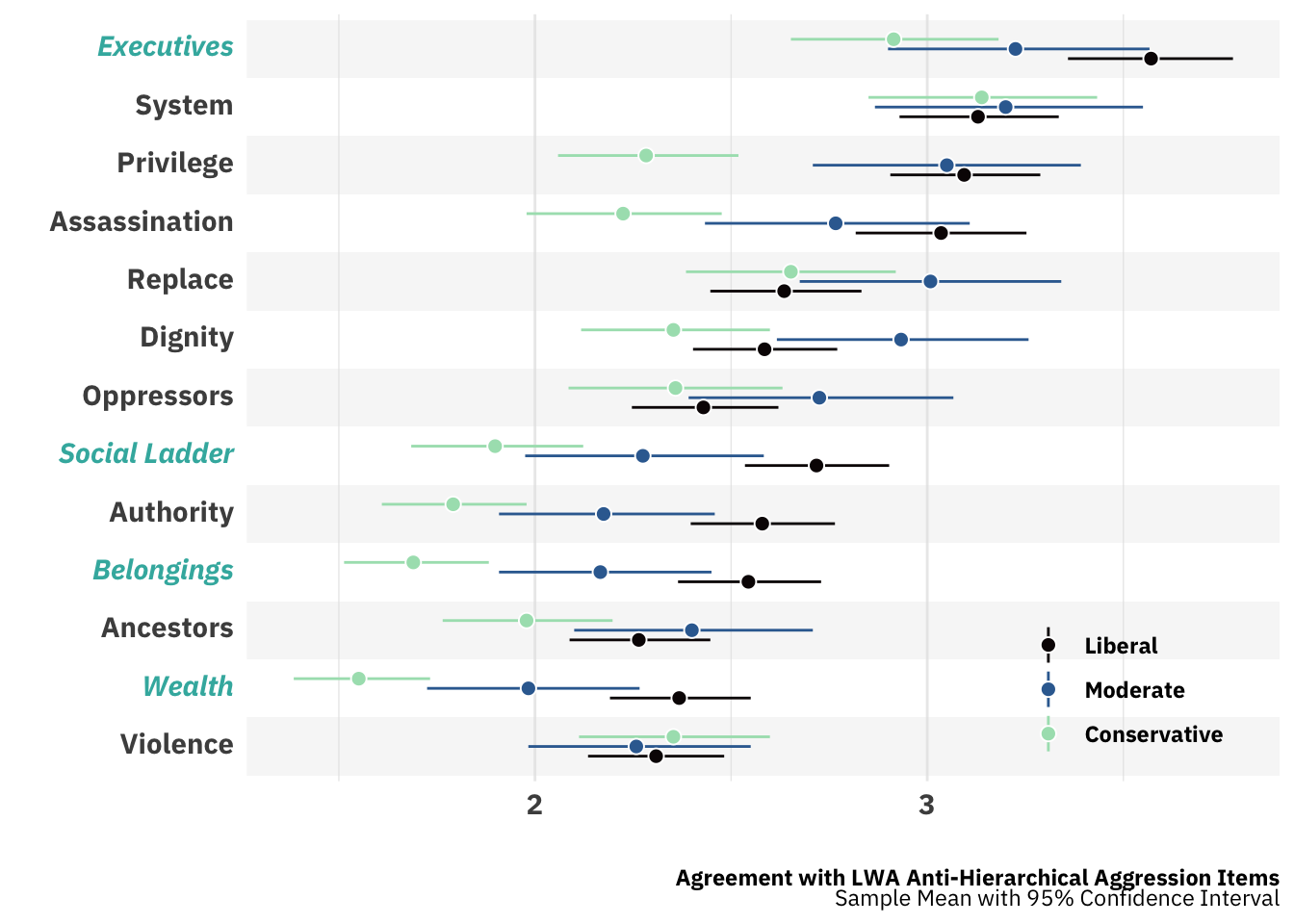

Anti-Hierarchical Aggression

We used the 13 items from the left-wing authoritarianism (LWA) scale developed in Costello et al. (2022) that tap the anti-hierarchical aggression facet of LWA. These were:

- If I could remake society, I would put people who currently have the most privilege at the very bottom.

- When the tables are turned on the oppressors at the top of society, I will enjoy watching them suffer the violence that they have inflicted on so many others.

- Most rich Wall Street executives deserve to be thrown in prison.

- Constitutions and laws are just another way for the powerful to destroy our dignity and individuality.

- The current system is beyond repair.

- We need to replace the established order by any means necessary.

- Certain elements in our society must be made to pay for the violence of their ancestors.

- The rich should be stripped of their belongings and status.

- Rich people should be forced to give up virtually all of their wealth.

- America would be much better off if all of the rich people were at the bottom of the social ladder.

- Political violence can be constructive when it serves the cause of social justice.

- If a few of the worst Republican politicians were assassinated, it wouldn’t be the end of the world.

- I would prefer a far-left leader with absolute authority over a right-wing leader with limited power.

Each item had seven response options arranged vertically below it, ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”. If you allow a humble researcher (me) to turn those qualitative responses into a 1 - 7 scale, the distribution of responses looks as follows:

Like the other scales, this LWA’s “AHA” has high internal coherence (Cronbach’s \(\alpha=\) 0.9, \(\Omega=\) 0.93). Unlike the previous two, this scale is a bit wonkier as far as ‘correctly’ ordering liberals, moderates, and conservatives. The keen eye will notice that it’s often moderates who are higher in anti-hierarchical aggression than liberals. It’s also a more ‘difficult’ scale: as a group, moderates are never at or above the scale’s midpoint (4). Again, no sigificant differences between treatment and control (not pictured).

One very interesting thing, though. You’ll notice that some of the items along the y-axis of the plot look like this. These items correspond to the statements I italicized in the list above and are the four items that explicitly mention “the rich.” They exquisitely differentiate among different ideologies. There are only two other items in the scale that differentiate like this, the “prefer a far-left leader” item (unsurprising that liberals would be more sympathetic to a left leader) and the “assassinate Republicans” item (and we now know there’s a taste for that). I think it’s really interesting that “the rich” is such a strong ideological trigger.

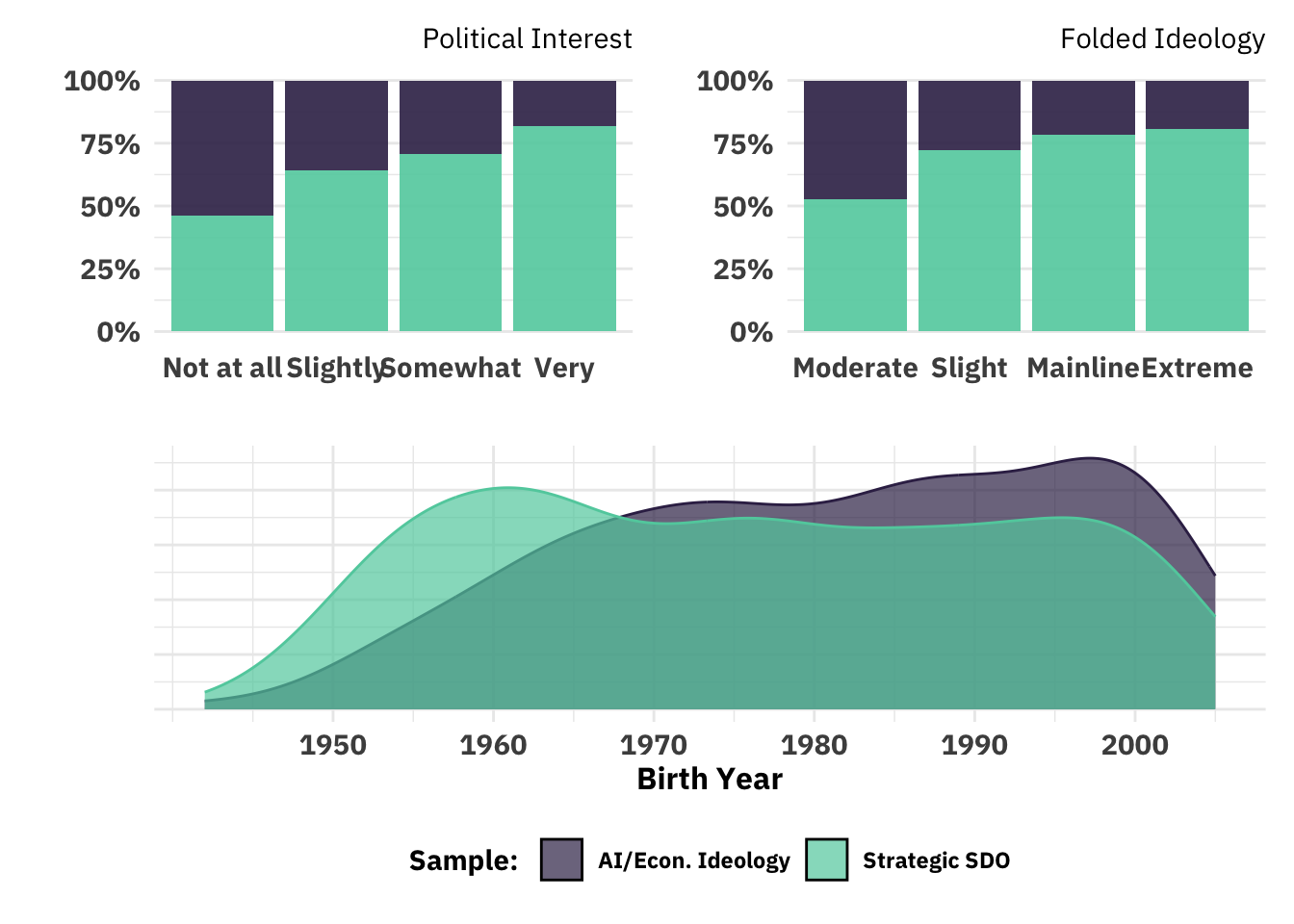

Bonus Information on the Sample (For Free)

As I mentioned a moment a go, this leaves me with a relatively small sample. It also skews the sample more ideologically moderate and less politically engaged/interested than the original sample.

29 If you want to know more about who ended up in this arm of the study, I would encourage you to go to the Strategic SDO post where I go through how those who identify with a side in the Israel-Palestine conflict (and consequently end up in the SDO arm) are different from those who do not (and are consequently included in the study discussed here).

The idea here isn’t to take away specific numbers, but to determine if you think the selection into this sample would change your interpretation of it. The upper left member of the triptych, political interest, breaks down respondents’ sample by their level of self-averred political interest. Only in the “Not at all interested” group is there rough parity between the two groups. “Not at all interested” is, though, by far the smallest group in the entire sample.

30 Political interested was measured with the question “How interested are you in politics?” to which people could choose among “{Not at all, Slightly, Somewhat, Very} Interested”.

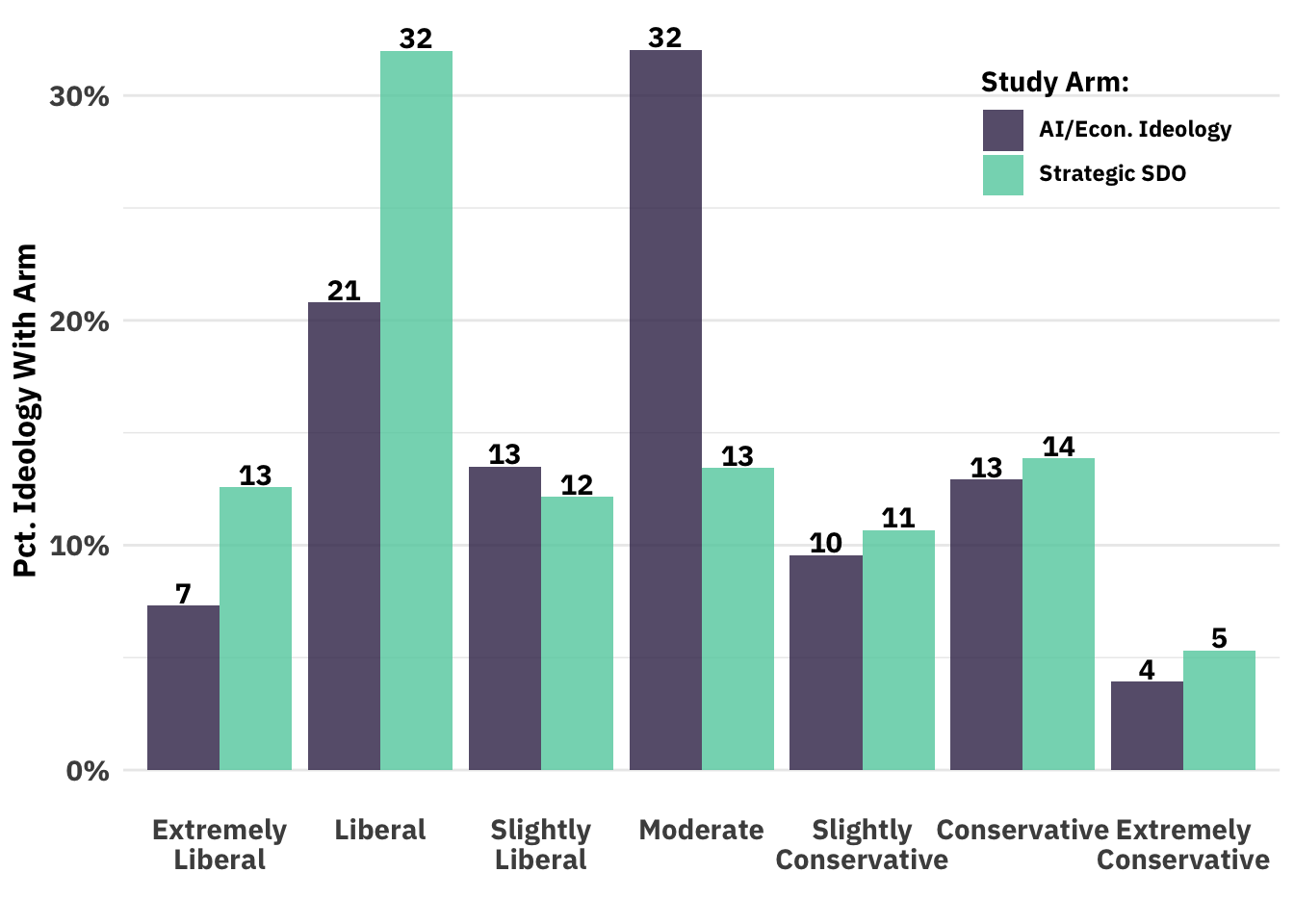

In the upper right, the sample is broken down by ‘folded’ ideology, whereby moderates form one group, slight liberals/conservatives are counted together as one group, same for four-square liberals and conservatives, and way out on the end, all people who attach “extreme” to their ideology are grouped together. Folded ideology shows a similiar pattern to interest. The soi-disant moderates are roughly equally split between the two samples, as were the not-at-all interested. For anyone who self-describes as slightly liberal/conservative, liberal/conservative, extremely liberal/conservative, they are much more likely to choose one of the two sides and send up in the Strategic SDO sample.

Lest you think that extreme ideologues abound in the one arm while moderates populate the other, you can imagine the following thought experiment. If this entire study had been done in person and each arm had 100 people in it, what would the ideological breakdown be in the respective arms? If the 100 people in a given arm were in a room, how many of them would be slightly liberal, extremely conservative, etc.?

The distributions are different. If effects were observed, the effect in the Strategic SDO arm would be more driven by liberals whereas the effect in this study would be more driven by moderates. How does that affect our findings? First, any differences between those in the positive versus negative treatment groups would still be a causal. There would be no “correlation does not equal causation”-ing this study. One could argue that the disproportionate amount of moderates in this study might make finding an effect easier because their economic ideology (such as it is) is less crystallized. Instead of being well-learned and bound up with their identity, it is more malleable and pragmatic. Or, alternatively, perhaps moderates are less ready to connect economic information with political views, making it less likely that an economic treatment will move political outcomes. Personally, I think ratiocination about potential heterogeneous treatment effects is still premature. ## Materials Appendix {#ma}

31 Premature at least with regard to political ideology and interest. As I will remark later, age (which proxies as ’amount of time exposed to new dispensation), wealth, and skill level should be relevant moderators.

All participants saw the following block of text

AI’s Upending of the Economy

The World Economic Forum estimated that Artificial Intelligence (AI) will replace 85 million jobs by 2025. In advanced economies such as the United States, about 60% of jobs will likely be impacted by AI. While some jobs will benefit from AI integration via enhanced productivity, the lion’s share will be made partially or completely redundant. This will likely lower labor demand, leading to lower wages and reduced hiring. In the most extreme cases, some of these jobs may disappear altogether.

Though we know that AI will reshape wealth and income distribution, the ultimate winners and losers of the coming AI revolution are far from obvious. Counterintuitively, those with traditionally “low-prestige” jobs involving manual labor or skills learned at community colleges could find themselves in higher demand and making more money than those holding prestigious degrees, as AI’s first targets are those with “the most highly compensated, highly creative, and highly educated work” (Mollick, 2024).

After reading that, they saw a screen with

Now, we’d like to ask you a few questions about your job and field of occupation that will allow us to estimate how you and people with your work profile will fare in the post-AI economy.

We already have your age, level of highest education, and income, so we just need to ask four questions in order to calculate the most likely effects of AI on your future employment.

And the four questions, with response options, were

- What is your current occupation? [Open-ended responses]

- What is your current level of flexibility regarding remote work? (Fully remote, hybrid, on-site)

- In what field is your highest degree? [Open-ended responses]

- In your current role, does your work primarily involve interacting with people or analyzing data and information?

- Mostly processing information and analyzing data

- Mostly interacting with people

I’m not sure I’ll do this again, but it was a learning experience.

Socialist/Laissez Faire Text

Here are the items (with color indicating those that are reverse coded)

- Many people who get welfare don’t really deserve any help

- The government should spend more on unemployment benefits, even at the expense of other government programs

- Most unemployed people could find a job if they really wanted one

- Luck explains people’s misfortune as much as anything else

- Management will always try to get the better of employees if it gets the chance

- There is one law for the rich and one for the poor.

- Working people do not get their fair share of the nation’s wealth

- Inequality continues to exist because it benefits the rich and powerful.

- Differences in income in the US are too large.

- It is the responsibility of the government to reduce the differences in income.]

Return to item results.